A Concrete Alliance: Modernism, Communism and the Design of Urban France, 1958-1981

French modernism has long enjoyed a privileged status in the history of 20th century architecture. The massive reshaping of French cities that took place at the hands of modern architects between 1958 and 1981 is commonly regarded as a unique episode when modernist ideals were tested on an unprecedented scale. The French urban architecture that emerged from this period has been historicized alternatively, as evidence of the influence of Le Corbusier, as a symptom of European capitalist development, as an episode in the history of colonialism, as the context for the invention of the grands ensembles, and as the theater for a social critique of modernism around the events of May 1968. Yet, the history of postwar French modernism has never fully accounted for the pervasive influence, throughout this entire period, of one of architecture’s most important institutional patrons, the French Communist Party (PCF).

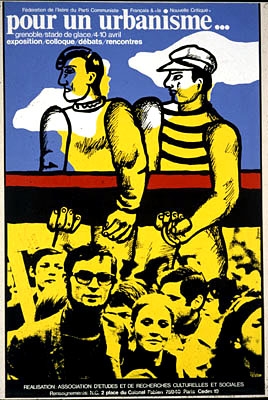

This dissertation contends that the PCF was a crucial agent to study the city as a modern architectural project during France’s postwar urbanization. Although communists’ ultimate ambition was a return to a national strategy rather than an ultimate dispersal of power, the PCF was an unwitting participant in France’s political decentralization, particularly from 1958 onwards. Then, the PCF took on the role of a paradoxical architectural bureaucracy on the municipal stage, on which it constituted its own planning infrastructures, appointed its own architects, and became almost a State within a State, producing an independent form of public architecture.

Architecture helped French communist elected officials to shape and program the city around projects that would anticipate social change on a meta-historical scale, while also contributing to the more immediate welfare of the working classes. Midsized French cities thus became sites of opportunity for architects pursuing political change through design. Sharing design agency with politicians, complicit in ideological, cultural and electoral endeavours, architects agreed on the city as a common project that represented both a means of political thinking, and a unit of governance, planning and design. Due to their early engagement with urban issues, communist-affiliated architects became among the first to confront shifting trends in urbanization, to appropriate French urban sociology, and to anticipate the crisis that the modern city would experience over the course of the 1960s.