Princeton University School of Architecture

Announces the Final Public Oral Exam of

Vajdon Sohaili

“The Shape of Unity: Architecture, Art, and the Designs of

Postwar Transnational Settler Colonial Community”

January 31, 2023, at 10:00 a.m.

Room S-118

Committee:

Spyros Papapetros (co-advisor)

Brigid Doherty (co-advisor, German and Art & Archaeology)

Eduardo Cadava (English)

John Paul Ricco (Art History, University of Toronto)

Abstract:

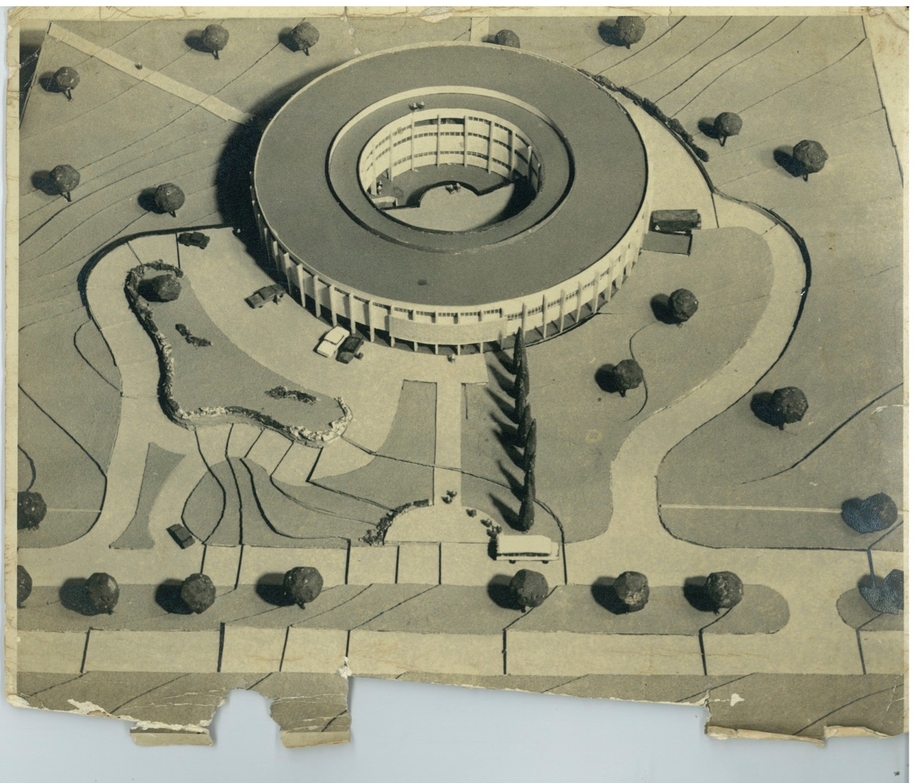

Following the 1945 signing of the United Nations Charter and the resulting waves of decolonization, projects of public architecture and art increasingly sought to shape conceptions of political community unified under idealized consensus. Yet, in contexts resisting decolonization—specifically, settler colonial contexts—such projects served to perpetuate settler interests, affirming non-existent, incomplete, or unwanted social harmonies. Analyzing public institutional architecture and public art—officially sanctioned works seeking to represent pluralist, humanistic ideals and interpellate collective self-understandings—in three post-WWII settler colonial societies, I argue that “unity,” “community,” and their contextual avatars supplied not only a logic for spatial design, but also a transnationally traded alibi for the perpetuation of settler power. First, in the former Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), a disingenuous policy of “interracial partnership” permits a White minority to defer Black majority rule, and results in the construction of a circular National Museum that monumentalizes settler archaeology. Second, preaching a doctrine of “oneness,” the Bahá’í religion constructs two monumental devotional buildings—one in the newly-constituted Israel, another in suburban Chicago—as twin base-camps for a global conversion campaign drawn along colonial lines and sustained by settlerism’s strategies of elimination. And third, in Montréal, against violent acts of separatism by Quebec-nationalists, expressions of social and artistic “integration” animate the construction of a massive performing arts complex and the techno-utopian idealism of Expo 67, both founded on Indigenous erasures. In each case, a public byword—respectively, “partnership,” “oneness,” “integration”—operates as a discursive surrogate of unity, channeling the populist appeal of community rhetoric, and shaping a program of cultural-institutional production driven by a complicit settler creative class of architects and artists. Reframing history and political mythology via spatial and iconographic conflations, these projects exhibit the erasures and clefts of settlerism’s eliminationist logic, while at the same time, channeling and repurposing the communitary idealisms associated with postwar modernism. Geographically diverse, but structurally and materially entwined, the three case studies examined here disclose a transnational settler typology of public-institutional architecture and art ostensibly oriented towards reparative notions of unity and community, but pragmatically arranged to forestall decolonial fragmentation.

A copy of the dissertation is available, for viewing only, in Room S-110 and the PhD/Green Room.